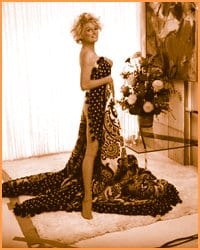

Before Totie Fields, Joan Rivers, Roseanne Barr and Margaret Cho, there was Phyllis Diller. An unapologetic ugly duckling, Diller was a pioneer in stand-up comedy when women were confined to the kitchen.

And like her comic successors, Diller first found favour with gay male audiences who cheered on a fellow misfit and iconoclast.

In her new autobiography, Like a Lampshade in a Whorehouse: My Life in Comedy (Tarcher/Penguin), Diller at 87 looks back on a half-century of show business with equal amounts of nostalgia and bittersweet candour. And she heartily acknowledges the gay men who managed her and the gay audiences who jump-started her career.

“Gay men have the most wonderful sense of humour,” says Diller, calling from her Beverly Hills home.

“And they are willing to laugh. They appeal to me and I appeal to them.”

A life of comedy didn’t seem likely at first. It was the mid-1950s and only men were stand-up comics. Diller was a 37-year-old beleaguered housewife from Alameda with five children and an eccentric husband named Sherwood.

“Sherry” was a perennial dreamer with grandiose airs and dead-end schemes. Diller affected a self-deprecating sense of humour to cope with a painful home life. Friends suggested she develop a stage act.

So, she took a break from advertising to work at the nightclubs of North Beach, the bohemian section of San Francisco humming with counterculture offerings: jazz clubs, strip joints, gay bars and beatnik hangouts.

Diller made her debut at a dark, musty North Beach club called The Purple Onion. When she came onstage in second-hand evening clothes, highlighted by a ratty fur piece and a cigarette in an elegant holder, the predominantly gay audience recognized a kindred spirit. She was immediately accepted.

Diller returned the favour. Her one-liners skewered her gawky looks and her domestic life, a shambles due to Sherry’s infrequent employment. But she never stooped to homophobic humour, although gays were an easy mark during the McCarthy era.

“No, no, no, no,” she says. “In fact, Joan Rivers and I both absolutely insist that we never would have got started without our gay audience. They were the first to actually accept us as funny women.”

The nutty broad in the hand-me-down gladrags, bold enough to point out the downside of marriage and suburban living, was developing a strong following.

Her first collaborator was a local man named Lloyd Clark. “Suave, dark-haired, pencil thin, and overtly gay,” as Diller recalls in her book, Clark helped Diller develop jokes for her act for $5 per hour.

Diller credits her start at The Purple Onion to a man named Barrymore Drew. A tall, elegant man always clad in sandals, Drew was part owner of the club. Drew was enchanted by Diller in her ill-fitting evening dress and rhinestone high heels. He hired her to perform six nights a week, where she shared the stage with singers, other comedians and an aspiring dancer-actress named Maya Angelou.

Under Drew’s tutelage, Diller developed new comic personas, from a fortune-teller to a gangster’s moll, and played for both locals and crowds that arrived in tourist buses. She earned $60 a week, barely enough to support her five children and sporadically employed husband.

Drew became Diller’s mother hen, grooming her career and even allowing her to stay on his Sausalito houseboat, a respite from Sherry’s spiralling career crises. Diller would often accompany Drew as he cruised San Francisco’s Fillmore district for men of colour.

“Oh, my precious Barrymore,” Diller says. “Well, here’s a gay man who’s just totally responsible for my first five years. He took care of me as a father would. He gave of himself.”

Throughout the book’s narrative, gay men are remembered with great affection. One is Rod McKuen, the Stanyan St poet-songwriter whom Diller met in the early 1950s, when she was a copywriter at radio station KROW. McKuen was a disc jockey.

“He was an 18-year-old child and here I was a 33-year-old woman, a housewife,” she says. “We absolutely bonded instantly because, you know, talent and creativity. He was a musician and a poet and a scholar. And I considered myself the same. And we simply loved each other and became just excellent soul mates. And it has lasted a lifetime.”

The two shared a cruise to the south of France just two years ago.

While not immediately well known to younger audiences, Diller has kept working throughout the decades. She voiced the queen in A Bug’s Life and had a recurring role on CBS’s daytime drama The Bold and the Beautiful-in her early 80s. After a heart attack in 1999, Diller got a pacemaker and returned to the stage. But she was slowing down and decided to retire in 2002.

She went out the old-school way, at the age of 84, with a farewell concert at the Suncoast Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas. Comedy royalty turned out for the event, including Lily Tomlin, Rich Little, David Brenner, Don Rickles, Roseanne, Ruth Buzzi and JoAnn Worley. The event is captured in a touching, if sometimes overly fawning, documentary by Gregg Barson called Goodnight, We Love You.

Calling herself the Madonna of the Geritol set, Diller displays the same self-mockery that made her famous. But she also fires off some topical gags: “I went to a gay wedding and I caught the jockstrap,” she observes, adding, “In San Francisco, a mixed marriage is a man and woman.”

Goodnight, We Love You has been screening at film festivals around the US, most recently the HBO Comedy Arts Festival.

At the height of her comic career in the 1970s, Diller switched gears and toured as a classical pianist, drawing on a formidable talent that first flowered during her St Louis childhood. Today, nearing 88, she no longer plays. (“God, that’s work. I’m very lazy.”)

Instead, Diller is a celebrated painter, working in “acrylic, water and spit,” she says, her signature horselaugh filling the phone receiver.

At the behest of friends, she holds an exhibition in her Beverly Hills home four times a year and people come to snatch up her vivid, Matisse-style tableaux.

When not painting, Diller keeps lunch and dinner dates with her inner circle of friends, which includes former governor Pete Wilson and his wife, as well as old Hollywood luminaries: Dolores Hope, the widow of Bob, and June Haver, a dependable gin buddy and the widow of Fred MacMurray.

And she still gets fan mail, which Diller answers personally with an autographed glossy.

Coming to the end of her list of daily activities, Diller pauses and notes, “Jesus, I’m busy.”

While her memories chronologically hopscotch about the pages, Diller’s recall is impressive. Asked how she refreshed her memory, she demurs. “No, no, I didn’t read anything. It’s all there; I just have to shake my head and it comes out.”

Looking back over eight decades, she says, was occasionally painful. But it gave her an illuminating perspective on her own comedy: the self-ridicule and stinging one-liners were a marvelous coping mechanism for what was often a very sad life.

“It took me to be over 80 years old-beyond that age-to realize that my act was actually very therapeutic.”

LIKE A LAMPSHADE IN A WHOREHOUSE.

My Life in Comedy.

Tarcher/Penguin, $36.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra