This content was created by Xtra’s branded content team alongside The Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives, separate from Xtra’s editorial staff. On Nov 18th, 2017 CLGA will host Flashback 3000, a night to celebrate a vision of the future in support of the archives.

When history is only a roadmap to avoid future potholes, it is a wasted resource, warns the executive director of the Canadian Gay and Lesbian Archives (CLGA).

Human nature means some things will continue to be repeated but “it’s important to know the work and the successes and the failures of what has happened before you so that you can continue to build on it,” Raegan Swanson explains.

“It allows the community to leave a legacy of what they’ve been able to do.”

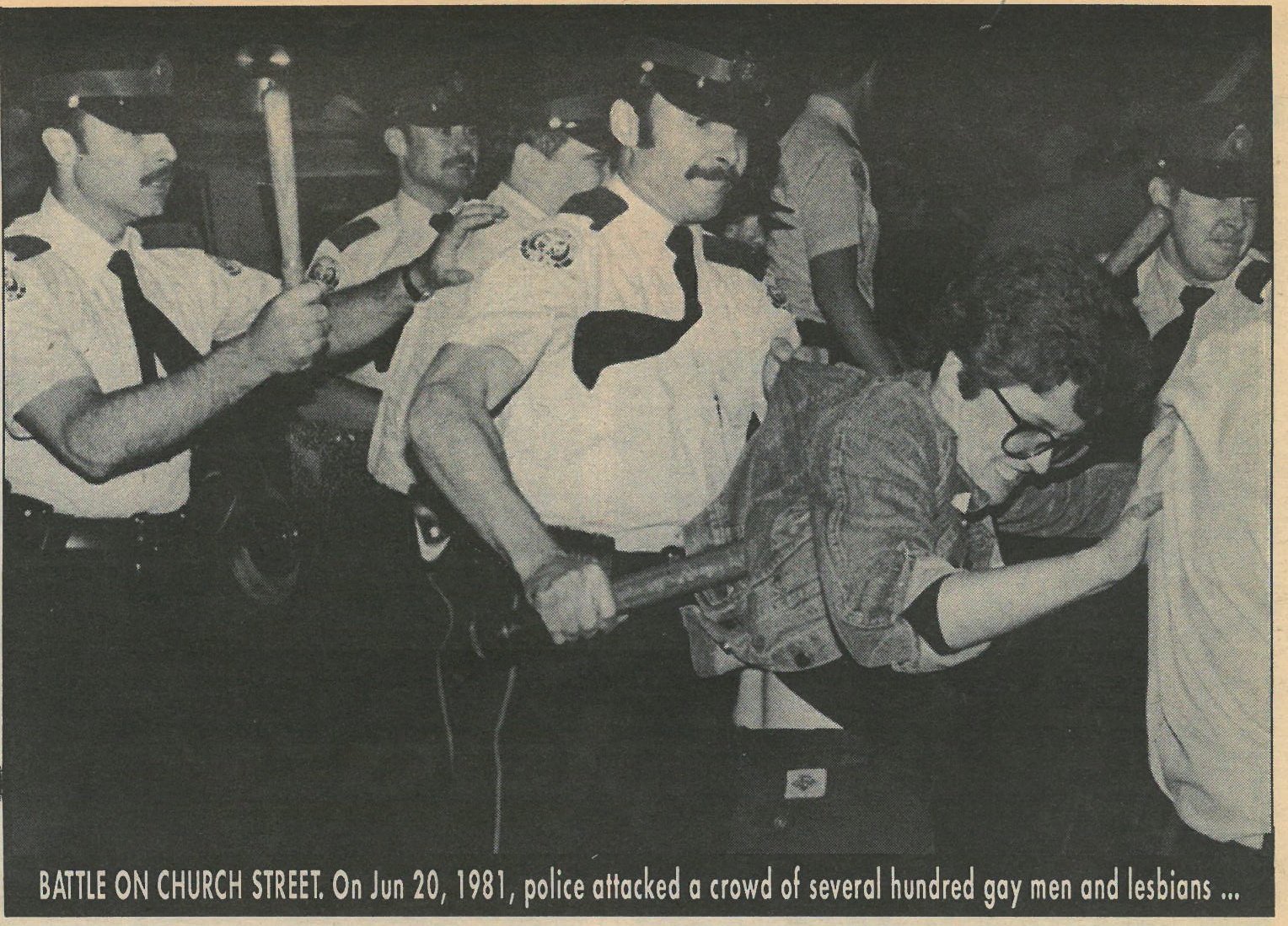

Take the infamous Operation Soap, for example, where Toronto police raided the city’s gay bathhouses in 1981 and arrested more than 300 men simply for having consensual sex. The community’s ensuing protests are often described as “Canada’s Stonewall.”

People protest in the streets of Toronto after the bathhouse raids on June 20, 1981. Credit: Courtesy Gerald Hannon

But the legacy of queer activism has even longer roots, Swanson points out. “I think it’s important to note that it wasn’t the first raid that took place. There were raids happening in Montreal before 1981.”

When Montreal police raided two gay spaces on Oct 22, 1977, they arrested 146 gay people in one night. As journalist Matthew Hays wrote in The Walrus in 2016, the ensuing community protests pushed Quebec’s provincial government to amend its human rights charter just a few months later to protect gay people from discrimination, making it the first Canadian province to do so.

Back in Toronto, despite a long overdue apology to the gay community in June 2016, Toronto police spent the fall of last year once again targeting and ticketing men who have sex with men in Marie Curtis Park. Some of the tickets have since been expunged and the police force recently acknowledged that it should have consulted the community’s LGBT liaison officer before launching Project Marie.

Though archives may not hold the keys on how to remove prejudices from those in power, the well-documented history of the 1981 bathhouse raids can provide some clear answers on how to respond to similar situations through protests and collective action.

“We have this history here in Toronto and people who were involved in various aspects have been able to contribute their stories to the CLGA, which means that people like me who were not born yet can use the documents and learn,” Swanson says, adding that she would like to see police really acknowledge their pattern of targeting minority communities and institute further diversity and inclusion training.

Another integral part to queer Canadian history has been the development of official Pride parades, the first in Canada taking place in Vancouver and Montreal in the summer of 1979.

“It’s huge now,” Swanson says of Toronto’s annual Pride parade. “It seemed to take forever for the parade to go by this year.”

But its size hasn’t guaranteed inclusion, Swanson notes.

As Black Lives Matter Toronto has pointed out, starting with a sit-in at Pride in 2016, many Black queer and trans people feel excluded by the celebrations, their voices pushed to the side and valued less than having police presence at the parade.

“I think now we’re seeing more acceptance of Pride parades as a thing but we still need to keep working to make sure it’s Pride for everybody,” Swanson says.

“What I think the protests in Pride can teach us is we can’t be complacent in our quest for equal rights,” she says. “There are still people that still have more privilege over others and we have to acknowledge that so that people have the same rights.”

Swanson says this is true to an even greater extent in other countries where being LGBT can lead to imprisonment or even death.

“Rainbow Railroad is doing a great job trying to help people from across the world,” she notes. The Toronto-based organization recently helped 31 Chechens flee pogroms at home.

But refugees fleeing persecution today still often face deportation to their countries of origin by the Canadian government. Sometimes they are granted asylum here, and sometimes their deportations are stayed after intense lobbying from advocates and groups like Rainbow Railroad and Rainbow Refugee in Vancouver.

Which is what makes organizations like those so important, according to Swanson.

“In Canada, we kind of assume that things are okay . . . and we forget that we live in a country that allows us to kind of forget that in other places, things aren’t going very well for people.”

All the more reason to preserve our community’s history, Swanson says, especially since she often hears that people feel alone when they’re coming out, transitioning or first trying to find community.

“It’s hard to find a community because you’re not necessarily born into it,” she notes.

But one place assurance, wisdom and similarity can be found is in the past. The CLGA has documented and preserved it to show young queer people today that it has been done before and can be overcome again.

“It’s hard to keep documents that show all the ways that you’ve been oppressed, or the trauma to your family,” Swanson says. “But they’re so important to show that you survived this, that your family existed.”

CLGA — Flashback 3000

Saturday, Nov 18, 2017

Bram and Bluma Appel Salon, Toronto Reference Library, 789 Yonge St, Toronto

Tickets available

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra