Transgressive literature. Last year the media bandied that expression about repeatedly. Why? Because Robin Sharpe was acquitted by the British Columbia Supreme Court of two counts of producing child pornography on the grounds that the writings in question were transgressive literature.

I’ll admit that, prior to this assignment, I wasn’t interested in touching the Sharpe case with a 10-foot pole. I had a vague idea what transgressive literature was, but I’d be damned if I was going to support Robin Sharpe in anything. Hopefully by the end of this essay, we’ll both agree why Sharpe’s acquittal on two counts of writing child pornography benefits us all.

What transgressive literature is exactly is hard to nail down. Anne H Soukhanov of the Atlantic Monthly described transgressive fiction as: “A literary genre that graphically explores such topics as incest and other aberrant sexual practices, mutilation, the sprouting of sexual organs in various places on the human body, urban violence and violence against women, drug use and highly dysfunctional family relationships, and that is based on the premise that knowledge is to be found at the edge of experience and that the body is the site for gaining knowledge.”

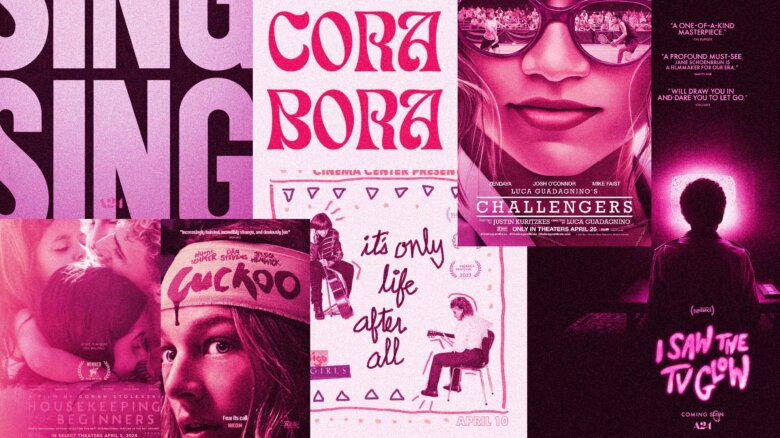

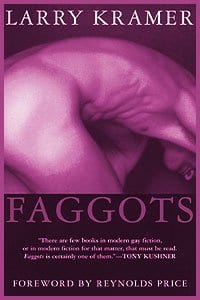

Acknowledged contemporary writers in this category include Dennis Cooper, Kevin Killian, Kathy Acker, Scott Heim, AM Homes and Gary Indiana. For forebearers, add William S Burroughs, George Bataille and the Marquis de Sade.

Sharpe’s trials shone light on this area of literature due to the testimony of a couple of experts. Justice Duncan Shaw’s decision notes that professor James Miller of the University Of Western Ontario testified that two Sharpe stories “Boyabuse” and “Stand By America, 1953,” “were in the Sadean tradition of transgressive literature…. He defined the Sadean tradition as focussing attention on transgressive sexuality. He said it represents the defiant breaking of taboos controlling sexual relations and practices established by the Holy Book, by literature and by taboo.”

Transgression in literature, though, is not only taboo content. Mark Macdonald, author and a buyer for Little Sister’s bookstore, argues that transgression is not limited to moral transgression.

“I think there can be aesthetic transgression that is certainly as important,” he says. For example, Burroughs’ cut up writing, which is “subverting the form as well as the content that, to me, is significant.”

UBC English professor Lorraine Weir, who also testified in the Sharpe trial, agrees.

“Stylistic transgression is at least as interesting as any straight up realistic narrative that has to do with actions that the bourgeoisie may find should be kept undercover. When you open your definition out like that – you know, this was James Miller’s point in the Sharpe trial – Dante is a great transgressive author, Chaucer’s a great transgressive author, King Lear is a great example of transgressive tragedy.”

***

Let’s say, then, that crossing beyond the established norms in content or style is what makes transgressive fiction. What is a norm today, though, in the here and now, is not the same tomorrow, nor is it the same the world over.

“I just read two books featuring sex with children,” says Arsenal Pulp writer George Ilsley, referring to Camilla Gibb’s Mouthing The Words and Meg Tilly’s Singing Songs. “Is sex with children transgressive lit? No it’s not, because these are two mainstream books.”

Tilly’s novel is published by major US publisher Penguin, and Gibb’s first novel won the Toronto Book Award. Taboo is relative to each individual in a particular time and a particular place. Context, perceived authorial intent and narrative tone or voice are as much a factor as the content in whether we regard something as transgressive.

Ilsley says that when writers put transgressive pen to paper, they are outlining where our culture, and each individual within that culture, have their limits.

“We’re drawing the map and holding it up and saying, ‘Look, there is a map. And this is where you are on the map.'”

The very notion of transgressive literature is going to move around, Ilsley says, because community standards are always changing. The history of literature is rife with what we now call classics but which were once denounced as obscene. Every available copy of Radclyffe Hall’s The Well Of Loneliness was burned by order of the courts of England once its publisher was found guilty under the Obscene Publications Act in 1928. Although the novel was acquitted in a similar US case two years later, the novel didn’t appear again on British bookshelves until 1949.

Perhaps the most famous case in last century’s history is Howl, Allen Ginsberg’s beat poem, which the San Francisco police seized from City Lights Bookstore in 1957 for being indecent and which is now used regularly in US classrooms.

So if transgressive literature helps us draw the map of our taboos, what’s the good in that?

“When I read Doing It For Daddy by Pat Califia,” says Macdonald of the SM fantasy novel, “it goes past my limit for what is erotic or what is compelling for literature, and yet in doing so it produces in me a reaction that is visceral. I feel it physically, which is different from reading Edmund White, where you might feel it emotionally. And as Pat Califia says, it’s important when you’re writing that you push your own honesty to the absolute extreme, that you talk about stuff that you don’t feel safe talking about.

“I think it can affect your perspective on the world. I think it can open new sorts of possibilities about how you see yourself in the world,” says Macdonald.

Ilsley points out that child abuse was not talked about until very recently.

“So even if the ideas of transgressive literature, or how they manifest, makes us uncomfortable, we have to remember the alternative is this horrible silence,” he says.

The alternative is living in a culture of denial. “My work has been linked to exposing hypocrisy,” Ilsley explains, “and that’s like a double standard in our culture where people believe two things at once. They know things aren’t okay but they don’t talk about it because somehow that’s even worse. If transgressive literature is one thing, the silence is the dark side of that force.”

Adds Macdonald: “If we can imagine the Lord Of The Rings’ world, then why can’t we imagine the Dennis Cooper world? Or the Anne Rice SM world? It’s the same thing. It’s fantasy. They’re as legitimate as one another. Fantasy is really important.”

But fantasy regardless of content?

“I would say the right to have those fantasies, yes, regardless of content,” Macdonald says. “I don’t believe that people act out on pornography. That’s something that the courts have also found. That’s something that has consistently been presented to the provincial supreme courts and also the Supreme Court Of Canada with Robin Sharpe. You’ve got lots of people telling you that, actually, you know, for active paedophiles, access to pornography is going to prevent crime, except in the cases where it’s actually produced through crime, you know, in the photographing of actual children or whatever, but that for somebody who’s compelled by their fantasies to be told that, no, they can’t explore or release those sexual fantasies, is what ends up [causing] violent behaviour.”

***

The influence of transgressive literature on behaviour is much debated in the courts.

Justice Shaw ruled that stories like Sharpe’s “Boyabuse” and “Stand By America, 1953” might glorify acts of sex and violence between boys and between boys and men, but “they do not go so far as to actively promote their commission…. Nor… send the message that sex with children can and should be pursued.

“I conclude that ‘artistic merit’ should be interpreted as including any expression that may reasonably be viewed as art. Any objectively established artistic value, however small, suffices to support the defence. Simply put, artists, so long as they are producing art, should not fear prosecution.”

The media may have had a field day describing Sharpe’s writings as horrific, but none of the press had access to any of the impugned material in question. That mystery itself creates problems.

What we fear most is what’s mysterious,” says Weir. “If we can get a hold of it, look at it, think about it, we can make up our own minds. We exercise our freedom to choose because we’re free to investigate those possibilities, but if texts are demonized, if that demonization rings bells for us for whatever reason – personal, political, religious, whatever – then we’re dealing with the irrational. We’re dealing with the whole force of the irrational, and that’s pure power, the irrational that we can’t tangle with. That’s what consumes us. Real texts that we look at everyday, we can just say, ‘That’s trash,’ and walk on. It doesn’t haunt us.”

Ilsley says we’re meant to be uncomfortable at the edge of free speech.

“The right of free speech is fundamental, but it doesn’t mean that I’m going to want to read somebody else’s free speech,” he says.

* Michael V Smith is the author of Cumberland, a novel which explores, among other themes, straight men who have sex with gay men in small-town Canada.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra