As I recall, I was at my desk at the AIDS Committee of Ottawa when then Capital Xtra editor Brandon Matheson invited me to lunch. We often lunched, generally in service of Brandon’s need for information. On this occasion, however, he sought not information but a columnist. Such was the culinary birth of Shades of Graydon. Mysteriously, Brandon believed I’d have something to say about Ottawa’s gay scene. Truth be told, I rarely knew what to write. Ultimately, it was a column about my grandmother Elsie’s passing (“Call Me Elsie”) that proved most relevant and popular. In it I described how my internalized homophobia rather than her external homophobia led me to withdraw during her final years. Fearing rejection, I’d isolated myself from the finest, smartest, most welcoming woman I had ever known.

That was in the early 1990s. Years when the vibrancy, strength and potential of Ottawa’s lesbian and gay community (as we then labelled it) was palpable. That there was a community was self-evident. If we’d asked that little red-haired girl featured in episodes of Kids in the Hall about the gay community, she’d have said, “It’s a fact.” Community, of course, is a shape-shifting, amorphous thing. In my present role as a doctor of sociology, I assure you that countless words have been penned in an effort to define it. From my then vantage point at ACO, it was clear I was employed during the golden age of Ottawa’s organized lesbian and gay community. As ACO’s coordinator of men’s sexual safety outreach, the reality of a community was beyond question. The social-services-oriented Pink Triangle Services was at the peak of its power and influence in that community. While the Association of Lesbians, Gays and Bisexuals of Ottawa was well into its twilight years, it remained a tangible link back to a proud past. Its progenitor, Gays of Ottawa, had been the first to speak of an Ottawa gay community. As a tactical move, in the early 1970s, GO activists constantly referred to a gay community. Not entirely sure a community existed, GO chose to manifest it in word and deed.

The early 1990s was a ferociously busy time, as individuals and organizations fought the good gay fight in Ottawa. Along with PTS, ACO and others challenged the ignorance of Ottawa’s sexual health services, Ottawa-Carleton regional police and others. The immense progress we witnessed was testament to a community effort and to changes wrought on a larger social canvas. Changing the bigger picture was the whole point, the raison d’être of lesbian and gay communities emerging in the 1970s. Communities that grew out of a nascent lesbian and gay movement that sought to create community as a political and social tactic, creating a constituency and ending isolation.

That lesbian and gay movement pulled together multiple threads to create a whole composed of difference. This larger fabric of diversity was tied by a common thread, namely the struggle for lesbian and gay rights. Originally, threads of real radicalism also ran through it to challenge notions of gender, sexual politics, sexual hierarchy and more. By the mid-1970s, such radicalism was largely put aside in order to secure gay rights. This “rights seeking” movement sought equality in areas of housing, work, citizenship and sexual practice. At the expense of the needs of lesbians, whose concerns pertained to reproduction, child custody and gender violence, the movement over-emphasized the sexual rights of gay men. And then, of course, the shadow of AIDS fell over us all. Slowly, however, the lesbian and gay movement expanded and rebalanced (somewhat) its rights agenda. Simultaneously, the communities of shared need the movement helped create continued to grow and evolve.

Which brings us back to now and my contemplation of a rebranded lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community. I find myself asking does — can — this community exist? And if yes, what thread ties that community together? Certainly some kind of community tangibly exists based on its unique service organizations, businesses and neighbourhoods. As a larger community of shared need and shared purpose, however, I think that kind of community is fast disappearing.

My mental meandering over our community landscape began years ago. At a friend’s same-sex wedding (another community success), an American guest asked me, “How’s the revolution going?” Without hesitation I answered, “It’s over — we won.” My American cousin was taken aback, so I assured him it had been an imperfect victory: homophobia and its beating heart, sexism, remained; queer youth were still bullied; transgender health and social needs are largely unmet; successful queer immigrants remain a lucky few. However, the movement’s primary goal of securing rights for the great mass of white, middle-class lesbians and gays was realized. “The mushy middle had been secured. Our radicalism drained away, our threat pacified by the satisfying of the needs of the many.” Bitterly but realistically I added, “Don’t kid yourself; the community’s not going to take to the streets to champion transgender health rights. In Canada it’s over — we’re done.”

What I fear is that the kind of unified community we once unhesitatingly spoke of, brought together by a shared purpose, has been undone by its very success. And successful we were for a host of reasons, but the unexpected result is that our shared basis for struggle and community is no more. As I described it for a sociology class, now that the big struggle is won, as a gay man I have little or nothing in common with the great mass of gay men save for our desire for other men — our love of dick. With a large number I, too, enjoy the community’s entertainments, its bars, baths, districts, transgressive camp sensibility. With a small subset I share progressive values; a lefty, feminist political stance. But with the gay community I’m not sure what I share. Fully aware of my awesome privilege as a white, healthy, able-bodied, middle-class, employed professional, I told the students that as I get older I’m not sure what gay community holds for me, in part because my privilege makes me less dependent on it. A lesbian and gay community remains one whose tangible manifestation I visit when I travel, spending time in gay districts, enjoying entertainments and openly shared desire. It is not, however, a community I live in or agree exists in ways we commonly speak of.

This is not to say that I don’t consciously come out, teach and identify as a gay academic as part of a continuing political project. What this says about a lesbian and gay community that once existed, however, I’m not sure. Social movements have a purpose, drawing people together, creating communities out of, and for, the struggle. In this we were astonishingly successful given the range of different groups, tastes and stances we drew into a whole. Interviewing the original members of Gays of Ottawa, I was surprised to hear that in the 1970s they never thought they’d see gay rights in their lifetimes.

As to the present community that we too readily assume still exists based on a shared definition and reality, it is one we would do well to reconsider if we are to understand what’s out there. There are still fights to be fought for queer youth, transgender persons, immigrants and our rapidly aging lesbian and gay populace. We still form community around issues, shared entertainments and desires, although these remain largely divided along gender lines, a fissure the movement was rarely able to bridge. However, we’re unlikely to come together as a community the way we once did or once imagined we did. Our movement did what it was supposed to, forming a (temporary) community in service of a political goal. The successful end of that movement for the mass of Canadian lesbians and gay men necessarily means the end of the particular kind of community it required and created.

What’s that old saying? “Be careful what you wish for … you might just get it.”

An excerpt from Michael Graydon’s first Capital Xtra column, published on Sept 24, 1993.

Chatting up a storm

Little difference between phone and phallus

My lesbian sisters will be left out on this one — gratefully, I suspect — but their gay and bisexual brothers now have local access to a chat line for boys. While not exactly gratis on behalf of Capital Xtra, it will, however, lead to much gratification.

Being an old hand when it comes to such lines, I seriously doubt — based on my own pernicious use — Mother Bell needed any increase from the CRTC. VISA is likewise deeply indebted to me for my ability to give good phone. While a local line will ease my long-distance feelings, will it lead to ever-greater discreet billings on my plastic?

It was AIDS that led many of us to begin to view the phone as a source of comfort equalled perhaps only by our beloved CBC. While video does the job for boys purely into “visuals,” a phone adds that touch(tone) of reality those hairless, California-muscled video-boys lack. True, phone lines are populated with more super-hung, muscled, studs than can be reasonably expected to exist. Truer still is the fact that your phone buddy may lie about everything in an effort to get you (both) off, but he’s still more real than those posable action figures we see in videos. After all, they’re just Ken-dolls on steroids that William Higgins found melting on the beach.

How many of us, though, will fudge? Not just the usual stuff like dick size, but the other stuff, like whether or not you have pecs. A high level of detail is often demanded by one’s phone buddy. Hair colour, height, muscle specs, hairy/smooth — “You don’t have any on your back do you?” — balls loose/tight, top/bottom, daddy/boy, saint/sinner, et cetera. In this visual era we apparently still need to have a picture drawn for us.

More on Xtra Ottawa’s 20th anniversary:

20 years of shining the light: Practising community journalism is vital, but it’s a difficult task

Our spaces, September 1993 — a look back at where Ottawa’s gay community gathered 20 years ago

Thinking back to Frontlash — Irshad Manji’s column sparked discussion and ruffled the status quo

Headlines from 10 years ago — Some of the stories from the 10th anniversary issue, Sept 11, 2003

Memoirs of an Art Fag — this ’90s scenester column tackled both politics and culture

Headlines from 20 years ago — some of the stories from our first issue

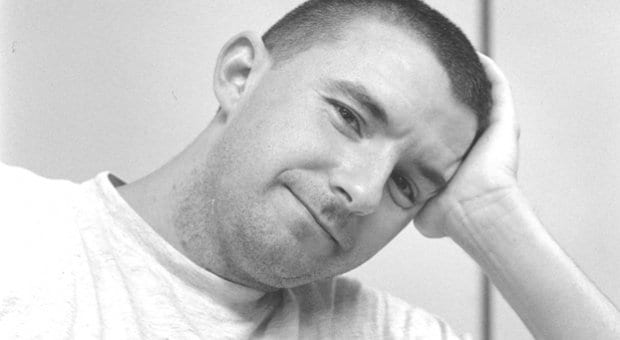

Michael Graydon is an associate professor of sociology at Algoma University. His column, Shades of Graydon, appeared in the first issue of Capital Xtra.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra